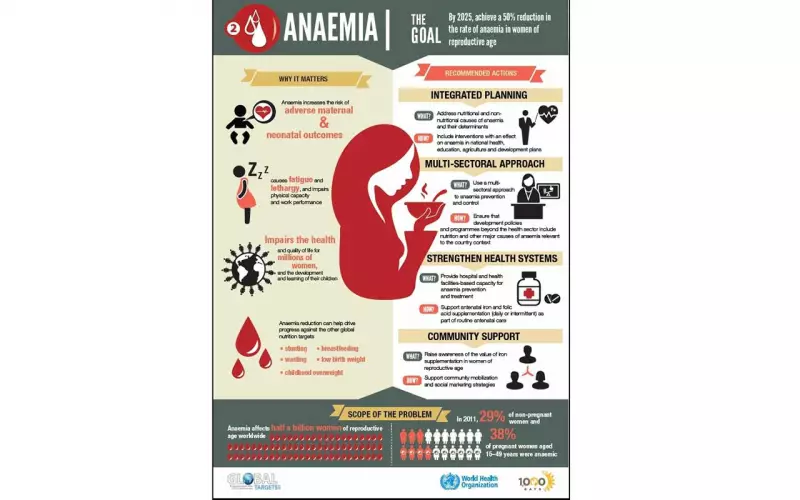

Nigeria and a host of other African countries have fallen short of the global target set for 2025 to significantly reduce anaemia among women of reproductive age. This failure has sparked urgent, renewed efforts to craft detailed acceleration plans, with sights now set on achieving a revised goal by 2030.

A Regional Reckoning in Senegal

The missed target was the central topic at a major regional workshop in Saly, Senegal, held in early 2026. Technical experts from the governments of 21 nations within the World Health Organisation (WHO) African Region, alongside key development partners, gathered to take stock of the disappointing progress and map out a new path forward.

The meeting aimed to move past mere promises and transform long-standing commitments into concrete, country-specific strategies. These strategies are meant to align with both global and continental health frameworks. The WHO African Region presented data showing that despite pledges dating back to 2012 to cut anaemia prevalence by 50% by 2025, not a single country in the region is currently on course to meet that goal. This stark reality forced the extension of the deadline to 2030.

Anaemia remains one of the most stubborn public health challenges across Africa, impacting millions of women and children. Its effects ripple out, hindering advancements in health, education, and overall economic development.

Nigeria's Persistent Struggle with Anaemia

In Nigeria, the fight against anaemia has been guided by national nutrition policies. The country first launched a National Policy on Food and Nutrition in 2002, later revising it in 2016 with ambitious targets for 2025.

These targets included slashing anaemia in pregnancy from 61% in 2018 to under 40%, boosting exclusive breastfeeding rates, expanding micronutrient supplementation, and improving deworming coverage for children. However, current data reveals that many of these benchmarks, from both the 2002 and 2016 policies, are largely unmet.

The Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS) indicates that roughly 55% of women of reproductive age suffer from some level of anaemia. The situation is even more dire for children, with about 67% of those aged six to 59 months affected.

A 2024 survey by the Federal Ministry of Health highlighted the complex causes of anaemia in Nigeria. It identified a web of overlapping factors including micronutrient deficiencies, infections, inflammation, and genetic blood disorders. For women and adolescent girls, iron deficiency is a primary driver. Other significant contributors are shortages of vitamin A, zinc, folic acid, and vitamin B12, alongside malaria, inflammation, Helicobacter pylori infection, and sickle cell disease.

Charting a New Course for 2030

Opening the workshop, Dr. Mbaye Sene, Head of Senegal’s National Council for the Development of Nutrition, called anaemia a major barrier to maternal health, child development, and national progress. He emphasised the need for collective responsibility and sustained commitment to alter the health outcomes for millions.

Dr. Ousmane Dieng, a Nutrition Officer at WHO, echoed this, noting that no world region is currently on track for a substantial reduction in anaemia. He said the workshop attendance reflected a shared determination to reverse this trend.

During technical sessions, national teams pored over data, pinpointed implementation gaps, and defined priority actions. Discussions zeroed in on integrating anaemia prevention and treatment into various health services, including sexual and reproductive health and community programmes. Governance, accountability, and mobilising resources were highlighted as critical for lasting progress.

By the end of the three-day meeting, each country had drafted an acceleration plan. These plans outline steps across the five action areas of the WHO's anaemia reduction framework, paying special attention to women and children, coordination, financing, and monitoring.

Development partners like Nutrition International, UNICEF, Action Against Hunger, and the African Union Commission reaffirmed their support, pledging technical and resource assistance to turn plans into measurable results.

Dr. Bruno Senge, Director of the National Nutrition Programme, explained how the workshop would guide national action, helping countries realign priorities with international recommendations. He disclosed that the Democratic Republic of Congo, for example, plans to finalise a multisectoral anaemia strategy and mobilise resources.

Similarly, Neema Joshua, a Deputy Director of Nutrition, stressed the need for a holistic approach tackling malaria, infections, and blood diseases alongside nutritional interventions.

The WHO stated that the outcomes from Saly show a renewed commitment to the 2030 targets and a growing recognition of anaemia as a cross-sectoral priority. While the challenge is complex, the agency insists solutions exist and political will is strengthening. Coordinated action, strong governance, and sustained investment could transform the lives of millions of women and children across Africa.