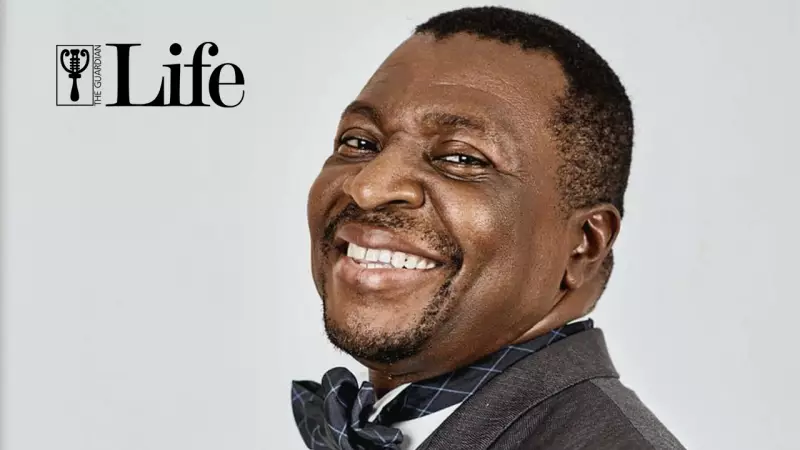

Ali Baba and the Business of Laughter: Building an Industry from Scratch

Ali Baba didn't merely construct a personal comedy career; he engineered an entire industry. Long before stand-up comedy became mainstream entertainment in Nigeria, he approached laughter as labor, comedy as professional service, and entertainment as serious business enterprise. His journey represents a masterclass in transforming passion into sustainable profession through strategic vision and relentless execution.

The Corporate Mindset Behind the Comedy

Atunyota Alleluya Akpobome, known universally as Ali Baba, dominated Nigerian stand-up comedy for decades with a business-first approach that revolutionized the sector. When he began his career, comedians were considered expendable entertainers—the first to be cut when budgets tightened and the last to be taken seriously in professional circles. Ali Baba changed this perception through deliberate positioning and corporate language that emphasized payment structures, value propositions, and market education.

He remembers clearly when stand-up comedy wasn't considered a legitimate profession in Nigeria—something you didn't pay for properly and certainly not something around which you planned major events. Through persistence and professional negotiation, he transformed comedy from optional filler to essential anchor in event programming.

Pioneering a Virgin Sector

Long before comedy clubs, streaming specials, and viral skit economies, Ali Baba describes stand-up comedy as a "virgin sector" in Nigeria. While performers like John Chukwu, Baba Sala, Papi Luwe, and Tunji Sotimirin preceded him, structured, paid comedy service didn't exist in organized form. What existed was primarily slapstick humor, novelty acts, and labor of love performances where laughter was free and payment was optional.

Ali Baba deliberately stepped into this gap with a revolutionary approach. He didn't dress like a clown or play exaggerated characters. Instead, he appeared on stage looking like someone who could just as easily be a lawyer or corporate executive—which was precisely his intention. He wanted clients to recognize comedy as professional service delivery: you booked him, he delivered quality performance, and he justified his fee through measurable impact.

Social Commentary Through Humor

For Ali Baba, comedy was never "just entertainment." He aligned himself intellectually with writers and thinkers like Chinua Achebe and Wole Soyinka, viewing comedians as social critics who use humor to reflect society back to itself. "You create laughter, and while people are laughing, you insert the truth," he explains.

From his university days, his material focused on observational humor about student union politics, vice-chancellors, and authority figures. As his platform expanded, he addressed military rulers, civilian presidents, social class dynamics, tribal tensions, and religious topics—though he maintained careful boundaries around sensitive subjects like rape and tribalism, recognizing the delicate balance between being funny and offensive.

Choosing Comedy Over Conventional Career Paths

Ali Baba was originally destined for law—his father's respectable, stable, clearly defined career choice. What changed his trajectory wasn't rebellion but practical evidence. During university closures following student protests against the IMF-backed Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP) in the late 1980s under Ibrahim Babangida's regime, he discovered his spontaneous remarks could command attention and generate laughter.

This ability quickly became economic currency. He began earning from performances what would have taken months to receive from home. In 1987-1988, when ₦100 monthly was substantial income, comedy offered not just financial reward but popularity, independence, comfort, dignity, and choice. It paid bills, put food on the table, and created options that aligned with his father's definition of meaningful work: providing food, shelter, respect, security for dependents, personal satisfaction, and moral alignment.

Building Infrastructure from Nothing

The subsequent journey involved patient, sustained groundwork rather than overnight success. Without event planners, managers, or mobile phones, communication moved through message centres, payphones, and intermediaries' notebooks. Sometimes a single person with a phone line controlled all bookings. Travel meant road trips in newspaper distribution vans or whatever transportation was available.

Most challenging was establishing pricing models. Convincing organizations to pay ₦10,000-₦20,000 for comedy services was difficult when salaried workers earned similar amounts monthly. Comedians were often dismissed as frivolous, overpaid, and unnecessary—first to be cut when budgets tightened.

Ali Baba responded with unprecedented industry branding, marketing, and corporate positioning. He placed billboards, ran print advertisements, and insisted on professional negotiations. Alongside fellow comedian the late Mohammed Danjuma, he formalized comedy and MC services as central rather than optional event components.

Turning Points and Industry Validation

Looking back, Ali Baba identifies four crucial turning points. First was an unexpected opportunity to calm a chaotic crowd, demonstrating comedy's power beyond mere entertainment. Second was introduction to Lagos by Eddie Lawani, connecting him to influential circles and larger platforms. Third was touring with major brands like 7Up and Coca-Cola, using comedy as marketing tool long before influencer culture existed.

The fourth and most defining moment came with a nationwide beer tour in 1996 featuring an unprecedented ₦1.6 million fee. After taxes, he retained ₦1.5 million—not just financial success but industry validation proving comedy had become serious business.

Evolution and Industry Expansion

As audiences grew, comedy material evolved through distinct phases. Early Nigerian stand-up relied heavily on ethnic and cultural stereotypes, followed by class divides (rich versus poor, Ajebo versus Ajepako), then education, language, and urban experience themes—each mirroring societal changes.

Platforms like Night of a Thousand Laughs accelerated industry growth, creating space for new comedians including Basorge Tariah Jr, Okey Bakassi, and Basketmouth. Ali Baba rejects notions that newer generations "pushed out" older ones, arguing instead that market expansion created demand exceeding any single performer's capacity, requiring more voices rather than replacements.

The Modern Comedy Landscape

Today's comedy industry is unrecognizable from what Ali Baba entered decades ago. Social media has collapsed time and distance, allowing jokes to circulate nationwide overnight and virality to manufacture visibility instantly. While entry barriers are lower—anyone can declare themselves a comedian—sustainability still depends on traditional principles: discipline, relevance, adaptability, and understanding value.

What concerns Ali Baba isn't competition but potential dilution—when speed replaces craft and attention replaces substance in comedy creation and consumption.

Legacy Beyond Nostalgia

Ali Baba speaks not as someone protecting his place but as someone documenting a process to prevent misunderstanding. Nigerian comedy wasn't gifted fully formed but negotiated into existence gig by gig, rejection by rejection, invoice by invoice. The industry younger comedians enjoy today was built deliberately, often without applause or recognition. This foundational work—more than the laughter generated—may represent his most enduring legacy in Nigerian entertainment history.