Politics

Oyetola Celebrates Bisi Akande at 87, Highlights His Democratic Legacy

Minister Adegboyega Oyetola congratulates elder statesman Chief Bisi Akande on his 87th birthday, praising his pivotal contributions to Nigeria's democracy and mentorship of leaders. Read more about his enduring impact.

Business

NESG Forecast: Naira to Trade at N1,480/$1 in 2026 Amid Economic Reforms

The Nigerian Economic Summit Group forecasts the naira will stabilise around N1,480 per US dollar in 2026, driven by rising reserves and policy coordination. Discover the full economic outlook.

Entertainment

Nigerian Woman in UK Nearly Loses Job Over Misunderstood Ochanya Video

A Nigerian woman in the UK shares how a conversation about Justice for Ochanya led to police interrogation and suspension. Her story sparks debate on workplace boundaries for migrants.

Security

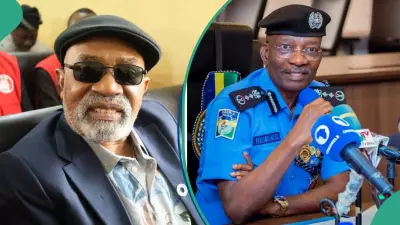

Anambra Police Kill 2, Arrest Gang Members Linked to Attack on Chris Ngige's Convoy

Anambra police engaged in a fierce gun battle, killing two suspects linked to the attack on Senator Chris Ngige's convoy. Weapons and a vehicle were recovered. Read the full details.

Sports

Education

Culture

Nigerian Lady Calls for Bride Price Ban, Sparks Debate

A Nigerian woman's viral TikTok video demanding the abolition of bride price has ignited fierce online debate. She argues the tradition promotes ownership and financial exploitation. Read the full story and reactions.

Mastering Nigeria's 371 Ethnic Food Traditions

Explore the rich culinary heritage of Nigeria, from communal cooking to 7 essential steps for mastering traditional dishes like jollof rice, egusi soup, and pounded yam. Discover how food defines identity.

Masquerade Attacking Singer at Ofala Festival Arrested

Anambra Police have arrested a masquerade for violent attacks at the Ofala festival in Awgbu. Read the full details of the incident and police action.

Man Leaves Faith Over Church's Snub of Late Senator Ubah

A dramatic scene unfolded as James Louise Okoye renounced his Christianity at a cathedral dedication in Nnewi, protesting the church's failure to honour late Senator Ifeanyi Ubah. Full story inside.

Lady Cancels Wedding Over Mother-in-Law's Remarks

A Nigerian woman shares why she called off her wedding in 2022 after her fiancé's mother made derogatory comments about her family's status. Her story sparks a major conversation on social media.

Health

Get Updates

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox!

We hate spammers and never send spam