Africa stands at a critical energy crossroads. While refineries are shutting down across Europe, the continent has a historic opportunity to achieve fuel self-sufficiency. Yet, a crippling cycle persists: nations build new refineries while remaining heavily dependent on imported crude and foreign refined products. This self-inflicted vulnerability paints a bleak picture for the future, especially as the United Nations projects that one in four humans will be African by 2050. This demographic boom will be meaningless if the downstream oil sector continues to suffer from chronic underinvestment.

The Precarious Reality of Africa's Fuel Supply

Imagine the continent cut off from fuel imports for just one month. The consequences would be catastrophic. Major cities from Lagos and Johannesburg to Cairo and Nairobi would be engulfed in endless fuel queues. Aviation would collapse, hospitals relying on generators would face blackouts, and water systems in megacities would fail. This is not a fictional disaster movie plot; it is the stark structural reality highlighted by the African Refiners and Distributors Association (ARDA).

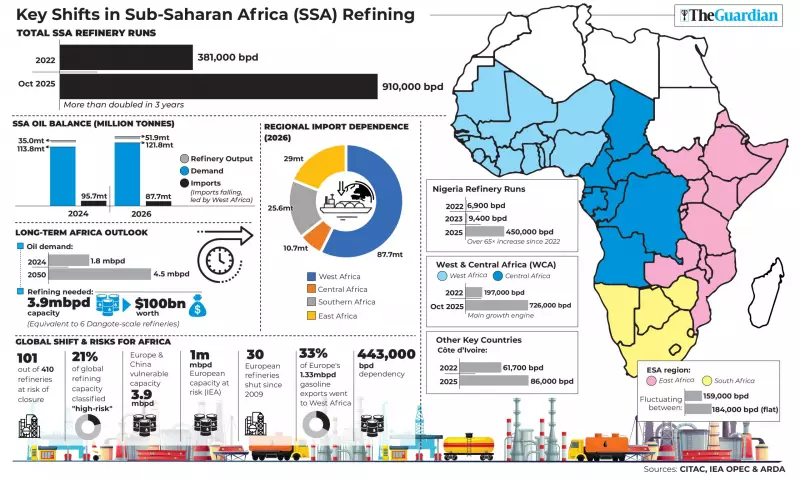

Despite producing over five million barrels of crude oil daily, Africa imports more than 70% of its refined fuel. This creates a single point of failure for every major economic sector. The global refining landscape is shifting against Africa, worsening the crisis. Wood Mackenzie forecasts that 101 of the world's 410 refineries risk closure in the next decade due to cost and emission pressures. Europe, Africa's primary supplier of petrol and diesel, is at the epicenter of this contraction, with at least one million barrels per day of refining capacity under threat.

Nigeria's Contradiction: Giant Refineries and Rising Imports

The situation in Nigeria, Africa's largest oil producer, exemplifies the continent-wide paradox. Data from the Nigerian Midstream and Downstream Petroleum Regulatory Authority (NMDPRA) for November 2025 shows a sector operating far below potential. Nigeria has an installed refining capacity of 1.125 million barrels per day, but utilization languishes below 467,000 bpd due to technical issues and crude supply constraints.

Between 2000 and 2025, Nigeria issued 47 refinery licenses, yet only four became operational. The Dangote Refinery, Aradel, Edo, and Waltersmith are currently producing, while the state-owned Port Harcourt, Warri, and Kaduna refineries—despite a $2.9 billion revamp effort—remain dormant. A critical revelation is that Dangote became Nigeria's sole source of locally produced petrol for a 14-month period, with the state-owned refineries supplying zero litres. This has created a risky single-supplier dependence.

Compounding this, Nigeria's petrol consumption surged unexpectedly from 47.5 million litres per day in October 2024 to 56.7 million litres by October 2025, even with prices above ₦1,000 per litre. This spike suggests issues with smuggling and demand management. Nigerians spent between ₦1.4 trillion and ₦2 trillion monthly on petrol, totaling ₦21.8 trillion in 14 months, underscoring an economy still structurally chained to petrol.

A Continent-Wide Push and Daunting Barriers

A wave of refinery projects is sweeping across Africa, representing its most ambitious attempt to close the processing gap. Ethiopia, Senegal, Angola, Uganda, and others are advancing projects that could collectively add over one million barrels per day of new capacity. In Nigeria, beyond Dangote, projects like the BUA Group's 200,000 bpd refinery and a planned 500,000 bpd facility by Backbone Infrastructure Nigeria Limited are in the pipeline.

However, immense barriers persist. Downstream projects often fail due to poor bankability and execution. Investors seek predictable feedstock, stable regulations, and enforceable contracts but frequently face policy inconsistency, infrastructure deficits, and currency volatility. Aliko Dangote himself highlighted the absurdity of importing crude from the United States due to difficulties sourcing it locally and the prohibitive cost of intra-African logistics.

A major hurdle is the lack of unified fuel standards. Africa uses 12 different gasoline grades and 11 diesel grades. Upgrading refineries to meet the African Union's cleaner AFRI-6 standard (10ppm sulphur) would require an estimated $16 billion. Inadequate ports, storage, and transport networks add $20–$30 per tonne to fuel costs.

The Path Forward: Integrated Solutions for Energy Security

Experts argue that solving Africa's refining crisis requires a holistic, integrated approach. Key solutions include:

- Prioritizing cleaner fuels by adopting the AFRI-6 standard continent-wide.

- Building interconnected infrastructure from ports and pipelines to storage depots.

- Ensuring regulatory stability and bankable offtake agreements to attract investment.

- Mobilizing domestic capital, including pension funds, for long-term infrastructure projects.

- Employing turnkey project delivery and robust risk-mitigation instruments.

The refining deficit is now a strategic obstacle to the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), forcing countries to rely on external supply chains instead of building regional ones. Without a decisive break from fuel import dependence, Africa's economic future remains precarious, vulnerable to the next global supply shock. The blueprint for energy sovereignty exists, but it demands coordinated action, not just bricks and mortar.