For many Nigerian women, whispers of family curses are a familiar backdrop to family gatherings. These stories often surface when an aunt becomes a widow or a daughter reaches a certain age without marrying. The tragedies are almost always tied to marriage and men—women who never wed, women who die after marriage, women who lose husbands or children.

A Familiar Theme Made Unsettling

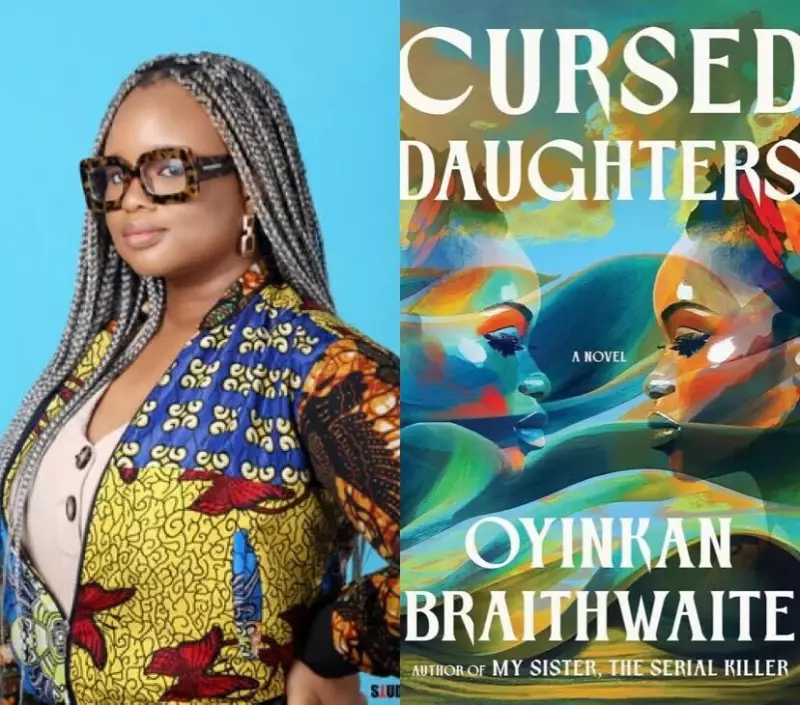

Entering Oyinkan Braithwaite's Cursed Daughters, this core theme felt recognizable. However, the profound unease that came from watching these patterns unfold through the Falodun women was unexpected. Their family felt so eerily familiar it was as if I knew them personally.

Oyinkan Braithwaite, the acclaimed Nigerian-British author of My Sister, the Serial Killer, ventures into new literary territory with this work. In a discussion with the Chicago Review of Books, she revealed she chose to challenge herself rather than write a sequel to her bestselling debut. She stated, "I wanted to try to do things I had never done before in my journey as a writer." This ambition is realized; Cursed Daughters presents a more mature and intimate narrative.

The Story of the Falodun Women

The novel opens at a poignant ending: the burial of Monife. Ebun, heavily pregnant and emotionally raw, returns from the funeral to find her Aunty Bunmi has already erased all physical traces of Mo—her photographs, her belongings, her presence. When Ebun confronts her aunt, her water breaks abruptly, sending her into premature labour.

Her daughter is born safely, but supernatural elements quickly seep into the narrative. Ebun dreams of Monife holding her newborn and wakes violently. Aunty Bunmi suggests consulting Mama G, a mamalawo (traditional spiritualist), if the strangeness persists. And indeed, things grow stranger.

The Origin of the Family Curse

The story then delves into Ebun's lonely childhood in the large Falodun house, marked by her mother Kemi's absence and a pervasive silence. Her life transforms when Aunty Bunmi arrives from England with her daughters, Tolu and the warm, curious Monife. Mo becomes Ebun's first real friend and compass, despite her unpredictable shifts from deep affection to withdrawn sadness. It is Mo who first tells Ebun about the Falodun curse.

The narrative rewinds further to its source: Feranmi Falodun, whose beauty captivated a travelling stranger. After their encounter, her family demanded a full bride price, formalizing what he viewed as a spiritual connection. Feranmi bore him twins, only to discover he had a first wife. A physical altercation between the two women led the first wife to pronounce a devastating curse: "It will not be well with you. No man will call your house a home... Your descendants will suffer for man’s sake. Ko ni da fun e."

This curse manifests as a cycle of broken engagements, unhappy marriages, and tragic losses that haunt the Falodun women for generations. Monife's story is its heartbreaking embodiment. Her relationship with Kalu, the "golden boy," was rejected by his mother due to the curse. In desperation, Mo visited a spiritual practitioner who instructed her to bind him through a blood ritual, a disturbing act that highlights the lengths to which women are driven when told love is not their destiny.

Kalu eventually married another woman but continued his affair with Monife. When both women became pregnant, Monife lost her baby, then lost Kalu, and ultimately lost herself, walking into a river and never returning. Her death becomes the ghost that lingers over the entire novel.

The Curse in a New Generation

Back in the present, Ebun names her daughter Eniiyioluwa, but Aunty Bunmi insists the child is Monife reincarnated, naming her Motitunde, meaning "I have come back again." As Eniiyi grows, her resemblance to Mo is uncanny—her hair, her mannerisms, her artistic nature.

The curse loops back when Eniiyi falls for Zubby. Ebun rejects him outright, and the reason is later revealed: Zubby is the son of Kalu, the very man who destroyed Monife. However, Eniiyi makes a pivotal choice. She refuses to let history repeat itself, ending the relationship before it can destroy her. She decides the curse stops with her.

Powerful Themes and Cultural Resonance

As a Yoruba woman from a large extended family, reading Cursed Daughters was a nerve-wracking experience. The Falodun household, with its aunties, children, secrets, and the large ancestral house built "just in case," felt intensely familiar. The novel also honestly portrays the religious duality common in many Nigerian homes, where devout Christianity coexists with consultations to mamalawos for matters of marriage and destiny.

Braithwaite uses the curse as a powerful metaphor for generational trauma. The trauma doesn't just haunt the Falodun women; they recreate it, believe in it, and live by it, making it a self-fulfilling prophecy. The novel powerfully explores womanhood as a burden and an inheritance of pain, where lives are bent around men who leave, die, or cheat.

In an NPR interview, Braithwaite offered a challenge embedded in the story: "If you are labouring under that kind of legacy, fight harder… It does not have to be your destiny." This sentiment forms the novel's true heartbeat, questioning the notion that women must accept suffering because their mothers did.

It is no surprise that Cursed Daughters earned a spot on TIME Magazine's list of 100 Must-Read Books of 2025. It is a deeply layered Nigerian novel that masterfully intertwines love, loss, lineage, and the painful weight of belief.